Coaching for Results

This article begins with the basic philosophy of coaching required for either behavior or strategy results. It then discusses key tenants and an approach for both behavior and strategy coaching, then concludes with challenges for executives who want coaching for results and coaches who want to deliver results.

Coaching for Results

A coaching philosophy underpins both receiving and giving coaching. Coaching does not mean doing but helping get things done.

Coaching has become one of those catch-all phrases like strategy, quality, or process. Because of its popularity, coaching has sometimes been misused. Those who use coaches sometimes are more excited about the prospect of being coached than about changing. One executive who was advised by his board to find a coach confessed after about 60 minutes of the first coaching session that he was really interested in engaging a “celebrity coach.” He could then tell his board and peers that he was being coached by a well-known coach which would give more credence to his leadership. Needless to say, coaching meant little to him and few competent coaches would succumb to work with him. This is like having a strategy or quality off-site training, but knowing that little will really change after the event. At times, those who declare themselves coaches are only a little more committed. When executives who retire early move into coaching as a transitory state between jobs, they fail to bring rigor to the role.

To overcome such generalities and misuses, coaching needs to move from platitudes to greater professionalism. Making coaching more professional requires a clear definition of the results of coaching. Coaching is not merely about a process of finding someone to confer but should have clear results that define the outcome of the engagement. In this article, I will suggest that there are two general coaching results: behavior change and strategy realization. Behavior change means that the executive being coached has behavioral predispositions that get in the way of being an effective executive. When specific behaviors are identified, examined, and modified, coaches help executives change. Strategy realization means that the executive being coached needs help to clarify and focus the business strategy to help the business achieve financial, customer, or organization goals. Of course, good coaching results are neither behavioral or strategy focused but require both for long-term results. When both exist, coaching helps craft an executive’s personal brand or identity that combines both personal behaviors and outcomes. But it is helpful to examine the premises of both behavior and strategy coaching so that they can be combined to help executives determine their personal brand.

This article begins with the basic philosophy of coaching required for either behavior or strategy results. It then discusses key tenants and an approach for both behavior and strategy coaching, then concludes with challenges for executives who want coaching for results and coaches who want to deliver results.

Philosophy of Coaching

A coaching philosophy underpins both receiving and giving coaching. Coaching does not mean doing but helping get things done. Coaches help athletes play the game better, even if they do not personally play the game. Player-coaches generally do not perform as well as sideline coaches. Executive coaches may not be the best managers, but they must be observers of good management behaviors and motivators for improved performance. In most coaching assignments, I try to observe a leader at work. In team meetings, I note how he interacts before the meeting (e.g., Is he formal or informal? Do people approach him or not?), how he manages a meeting (e.g., Does he follow an agenda? How does he make decisions? How does he treat the people during the meeting?), and how he follows up after the meeting (e.g., How does he check up on the decisions made during the meeting?). These observations come from observing the nuances of behavior and their consequences.

Coaching is not about the coach but about the person being coached. Being able to help someone recognize their strengths and weaknesses and how they can improve requires that the coach be a facilitator, not owner, of change. The executive being coached has to own and accept both his good and bad behavior. Coaches won’t make change happen or stick; they will simply help set conditions and circumstances that help others change. To keep ownership focused on the client, I keep asking them, “What do you want?” and then try to show them that their behaviors are unlikely to lead them to their goals. Clients define the desired outcomes and then we work together to help them reach their goals.

Coaching is both a learned art from experience and a disciplined science from education. Becoming a legitimate coach is a catch-22. Those you coach must have confidence in you, yet you don’t earn confidence until you have coached others. Early coaching experiences may begin with friends and allies who trust you and whom you can help and counsel. Like sports coaches who learn from being assistant coaches at high school or college levels before becoming head coaches in the pros, management coaches master their craft from working in the managerial trenches. My early coaching was often with those whom I had known in other settings (e.g., an executive from an executive development course) who trusted me. Over time, as I matured as a coach from successes and failures, I was more likely to be invited to coach those whom I did not know beforehand.

Coaching is ultimately a relationship. Sometimes the smartest and most technically proficient people are not necessarily the best coaches. Coaching requires sharing information and ideas in ways that change behavior and accomplish strategies. Coaches are not measured by what they know but how they help others change because of what they know and do. Transfer of knowledge flows from relationships of trust, so coaches must be credible and trusted by those they coach. In most of my coaching relationships, we start by getting to know each other. This requires listening and learning to understand the person I am coaching and sharing with them some of who I am. Building a personal bond and professional affection founds the coaching process. In many coaching assignments, we have begun by talking about a wide array of personal issues including hobbies, families, and personal goals. Once the executive knows I care about him or her personally, we can begin the more rigorous process of executive coaching. Until a relationship of trust is forged, coaching is more rhetoric than results.

Coaches may be from inside or outside the company. Those from inside know the subtleties of the company, the network of relationships within the company, and the likely impact of their counsel. Those from outside the company often have credibility based on external validity, bring innovative ideas to the coaching experience, and may be candid when insiders might temper their remarks. For internal coaches to be credible, they must develop an independent streak; for external coaches to succeed, they must discern organizational nuances. Most of my coaching has been from the outside as an external consultant, but in many cases, I have partnered with an internal coach (e.g., HR professional) who would help the business leader in more day-to-day routine transactions while I would do episodic coaching around events or in predictable time frames (e.g., every six or twelve weeks).

Coaches may not be popular. Giving blunt feedback about behavior or strategies may be personally risky at times. Giving feedback helps only if the feedback helps the receiver change behavior and accomplish goals. Often executives self-delude themselves because too few have been honest with them or because their self-confidence overwhelms their self-awareness. Constructive feedback concentrates on behaviors not the person, focuses on the future more than the past, and helps the person self-discover. I recall having collected 360 data from a leader where the data showed significant concerns. I set the stage for sharing this data by reminding him that without struggles, we do not make progress, and that only through honest looks in the mirror can anyone improve. Then we examined the data together and non-defensively worked to figure out why it was given as it was, what it meant in terms of his behaviors, and how he could productively respond. The concept that “we judge ourselves by our intent and others judge us by our behavior” has been useful. This philosophy has helped me coach executives and has helped them see that their intent may have been to clarify and focus attention, but their rather abrupt and direct questioning of employees may have communicated a lack of sensitivity and concern. Coaches must bring unfavorable views to the surface and deal with negative data in helpful ways.

Coaches probe through questions that require self-reflection. Learning is more powerful when the learner learns by choice rather than by edict. Coaches who pose insightful and timely questions help executives see the impact of their behavior on others thus helping executives improve. Some of my favorite questions are “What do you want?” to help focus on goals and purposes; “What are the options?” to generate out-of-the-box alternatives and become real; “What are the first steps?” to turn ideas into practices; “How would you know?” to define measurable outcomes; and “What is the decision you can make now to make progress?” to focus attention. These and other questions help the coach engage the client in reflection so that the client owns the result and the process of achieving the result.

These maxims form a coaching philosophy that enables a coach to help an executive deliver both behavioral and strategic results.

Behavior Results

Changing behavior is not easy. We know from research that about 50 percent of an individual’s values, attitudes, and behaviors come from DNA and heritage; the other 50 percent are learned over time.1 This split means that while we each have predispositions, we can also learn new behaviors. I am predisposed to be an introvert, to find energy in quiet personal moments, and to avoid social crowds and public settings. Yet, I do presentations for a living where I have learned to engage with others in extroverted ways. When working to help leaders change behaviors, it is helpful for them to recognize their predispositions but not to be bound by them. One executive preferred the more private anonymity that came from forging close personal relationships with his team and those he worked with. But, when his company was under siege, he realized that someone had to be the face of the company to the public. While not predisposed to this role, he accepted the challenge and worked to prepare and deliver public support for the company. While he became quite gifted at the public role—appearing on news programs, being interviewed by the media, and even doing commercials—he was never fully comfortable in it. An implication of the 50-50, nature-nurture, born-bred debate is that while the past sets conditions on our behavior, our behavior is not preconditioned. Any leader can modify behavior through effective coaching. Below are some of the hints for doing coaching for behavioral results.2

Know Why

Until there is a need for change, change will not occur. Once clients understand why they should change, they are more likely to accept what they should change. One senior executive had been promoted quickly due to his talents for analytics and detail. He was renowned for high-quality work. But, when he became the general manager of a large division, his attention to detail and analytics kept him from doing the more generic strategy work required in his new role. In our early coaching work, it was clear that he was more predisposed to working on details than strategy. To help him transition into his general manager role, we spent time defining the competencies of a successful general manager. As he benchmarked himself against the competencies we defined, he realized his strategic short comings and was more willing to explore new behaviors required to fulfill his new role.

Collect Data

Often single events or observations from single individuals are episodes not patterns. Coaching should be about patterns. Generally, people can identify their strengths more than their weaknesses, and collecting data from others helps face a true reality. Leadership 360s provide a marvelous source of data. The 360 may be through interviews or a survey of an executive’s subordinates, peers, and supervisors. With full spectrum data, the 360 will provide a wholistic view of the executive’s relationships and highlight areas of strength and weakness. 360 data enables the executives to compare self-perception to the perceptions of different stakeholders (e.g., Does the executive manage up or down better than across?). Another source of data is to track executive time. In one coaching engagement, the executive wanted to be more customer-centric. So, for two weeks, she kept a time log of who she spent time with, where she spent time, and what issues she spent time on. This time log was somewhat like a personal video or like someone who wants to lose weight writing down everything they eat. It was quite easy to review the data with the executive and observe she tended to respond to requests more than proactively investing her time. And, customer requests were low on her demand list. The data from a 360 or a time log helps the executive more accurately see what changes can and should be made. This data also serves as a baseline to track improvements that may be obtained through the coaching.

Prioritize

Not everything worth changing can or should be changed. In behavior coaching, it is critical to identify the one or two key behaviors that most need to be changed and that will have the most impact. One executive was losing credibility with his peers and the head of the company. In interviews, a number of concerns came up, including his lack of ability to engage others, his inability to focus, and his lack of tact in communicating desires. But, when asked “What one thing should he work on to be a more effective leader?” the response consistently was to be more brief in his comments. Evidently, the executive had a tendency to give long-winded answers to seemingly simple questions. With this input, the executive prioritized brevity as a behavior change. He started to track how long he spoke in meetings and other forums. He tried to keep his remarks to less than 45 seconds. His trusted administrative assistant gave him daily feedback of how often he kept to his 45 second rule. He improved and as he spoke less people sensed that he listened more. There is a silly line in change that applies to prioritizing behaviors: “By the yard it’s hard, by the inch it’s a cinch.” Some troubled executives have many things to work on, but they should find one or two specific behaviors that will be visible, impactful, and doable.

Be Behavioral

Abstract goals will result in abstract changes; specific behavior goals will result in specific changes. Sometimes the results of interviews are generic: “She is not a good people person.” In these cases, it is important to go deeper and identify specific behaviors that cause the conclusion. Deeper probes generally focus on situations: “Can you think of a situation where she treated people poorly? What specifically did she do? What could or should she have done differently?” Behaviors are observable and visible. I have asked executives to envision someone following them around with a video camera. What behaviors would the video expose? In becoming better with people, the video might reveal the executive not looking at people she talks to, not calling them by name, not paying attention when others comment, and being quickly distracted when in conversation. One executive learned that he went too often to his BlackBerry®. When he felt he had what he needed from a conversation, his mind would wander and he would look at his BlackBerry® for other incoming messages. This simple behavior communicated to his subordinates that he was not focused on them. By recognizing this behavior, he was able to limit it.

Focus on the Future More than the Past

Coaching is not therapy. In cognitive or psychoanalytic therapy, the therapist works to identify underlying causes of a behavior. Often these causes are masked, but rooted in past experiences or previous relationships with parents or others. Competent therapists have the ability to uncover and unlock how the past affects the present. Coaches do not need to be therapists to focus on behavioral change. Behavior coaching identifies what behaviors are causing dysfunctions then focuses the executive on the future and how to behave differently. An executive who wants to improve customer relationships needs to prepare an anticipatory time log where time with customers and on customer issues is woven into the calendar. An executive who wants to improve in people skills can learn to ask more personal questions of employees and peers, to focus full-time attention on the employee they are interacting with, and to express gratitude for an employee’s good work. These behavior changes generally do not require the intense psychoanalytic work a therapist might provide.

Go Public

Commitment goes up when we go public and become personally transparent with our intentions and desires. When an executive has identified an area to improve, it is helpful for the executive to share this commitment with others. This may be in a staff meeting where the executive thanks the staff for being candid with the coach in interviews then shares with the staff the conclusions from the interviews and publicly states what she will work on. This transparency lets the team know that the executive has heard their comments and is working to improve a specific behavior. In almost all cases, executives who are personally transparent will engender respect and confidence from their peers and subordinates as they work to change their behavior. The executive who savored details told his team that he knew he would rather be doing the detailed work but that he was going to commit to spending less time on details and more time on vision and strategy. He asked that his team make sure that the details were done well so he could focus on the longer-term issues. He also asked his team to quietly remind him when he was falling back into his detail traps.

Find Support

It is hard to clap with one hand and it is hard to change by oneself. Almost every executive I have seen who has made behavioral changes has had enormous support from trusted advisors. Many executives have an administrative assistant who is in constant contact with the executive. I frequently invite executives to engage their administrative assistant to give them daily or weekly views of how well the executive is adopting new behaviors. Executives open to such input will be much more likely to change. It is often difficult for high-powered and successful leaders to hear criticism, but when they ask for it and when it is framed as support for future success, they are more prone to listen and act. At times, it is also very helpful to have support from non-work friends since behaviors at work and at home are often the same. Executives who share with their spouse or children what they are working on often find enormous support.

Start Small, Keep Going

Most large change starts with small steps. Once executives have picked a behavior that they want to change, I have found “four threes” a helpful way to embed the behavioral change.

- Three hours. In the next three hours what can you do to exhibit the new behavior? This is probably not something dramatic but should be specific.

- Three days. In the next three days, what can you do to demonstrate sustained commitment to the new behavior? Quietly but consistently practice the new behavior. This may affect what you read, your language, your personal demeanor, and the way you relate to others.

- Three weeks. In the next three weeks, make sure that the new behavior change shows up in activities and relationships. Calendar times when the behavior change will be evident (e.g., dedicating time with customer groups or a brief staff meeting to talk about work processes). Continue to practice the new behaviors and receive frequent feedback on how you are doing.

- Three months. After about three months of working on the new behavior, if you continue with it, it begins to become part of your identity, and others will treat you accordingly. When your leadership identity, brand, or reputation becomes something others expect in you, you will be more likely to live it.

Like all new things, at first, the new behaviors may be difficult, but after three months, they become a redefinition of your personal brand. As others come to expect things of you, they begin to be more natural.

Learn

Learning should be less an event (let’s go off-site and talk to each other) and more a natural process. The best learners are inquisitive, self-reflective, and adaptive. They are constantly asking what works and what does not, then trying to put those insights into a future context. Executives who demonstrate learning agility are more likely to succeed. Overtime, coaches should be replaced by self-observation. When executives have the capacity to self-observe and self-regulate, they learn and grow. Sometimes this learning can be formalized through after action reviews where executives debrief their teams on how they perform, and at other times, it may be more personal where executives write in a journal, have a personal tally sheet, or share with a friend what they are learning.

Follow Up

Finally, behavior coaching needs indicators of progress. The greatest success is when the executive can track behavioral change. This is why data collection early in a coaching engagement is so important. Readministering a 360, redoing interviews, or debriefing the behavior change process enables an executive to monitor progress. If behavior change did not occur, the coach did not fulfill his assignment. Marshall Goldsmith boldly states that he is not paid unless the executive changed behavior as seen by others. This is not just clever marketing, but a real dedication to making sustained behavior change happen.

Coaching for behavior change changes behaviors. The end result is that the leader personalizes a new set of behaviors that may work for him. As learned behaviors become natural acts, leaders change their identities and reputations.

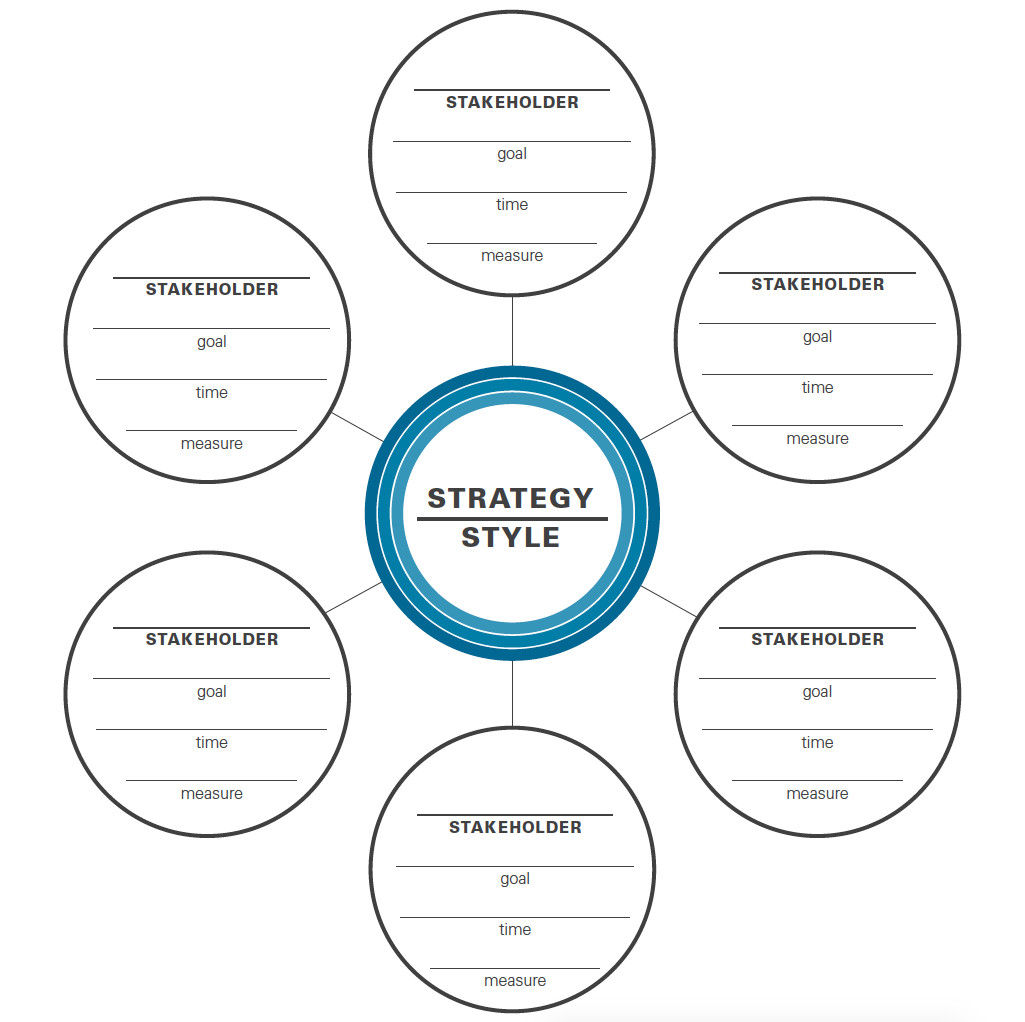

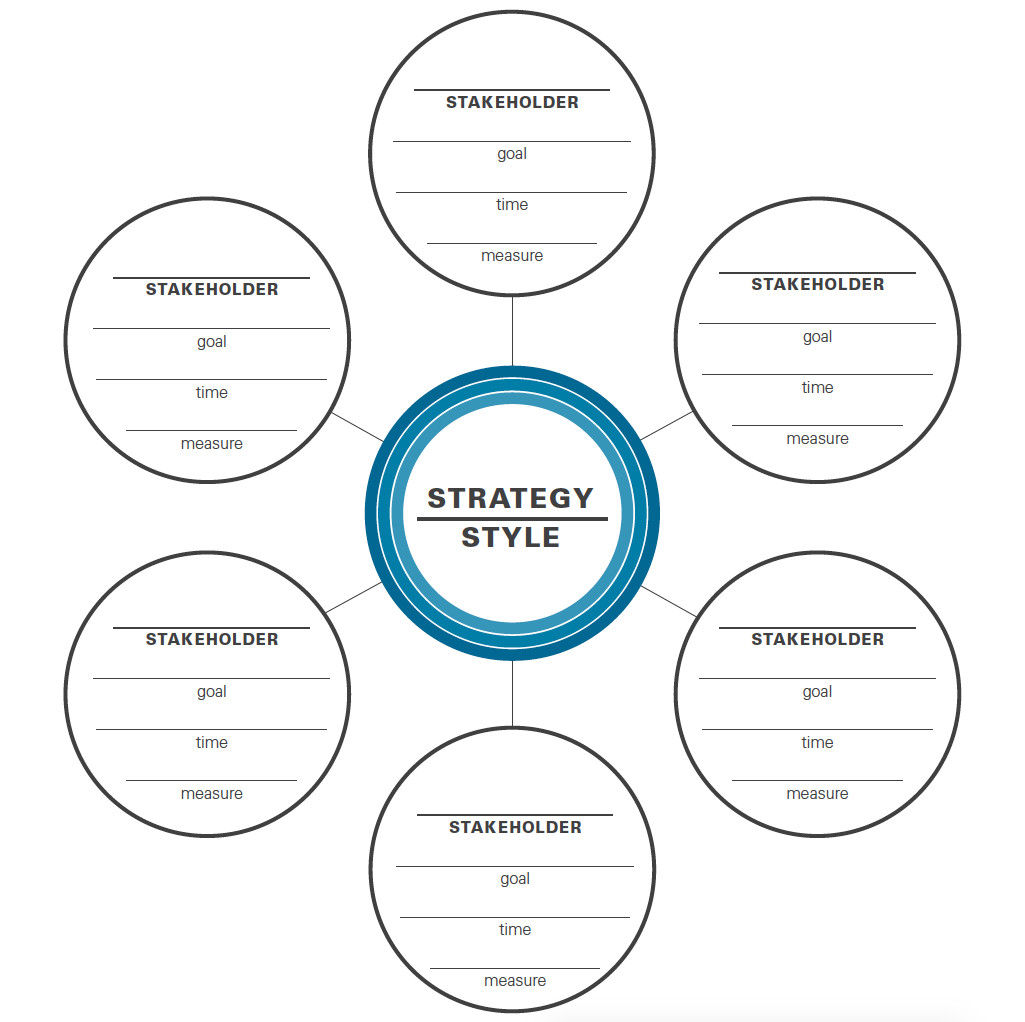

Strategy Results Process

Strategy results coaching focuses more on helping the executive gain clarity about the results he hopes to accomplish and how to make them happen. It is less psychological and more organizational. It also builds on the philosophy of trust, relationship, and collaboration, but focuses this philosophy on helping the executive clarify and reach his goals. In my strategy coaching, I have adapted the following steps depending on the situation. Figure 1 is the summary of this coaching process. At first glance, this is a complex figure, but each step enables me to draw and build this figure and coach a client through a behavior or strategy process.

Step 1: Clarify Your Business or Organization Strategy

Every executive works for an organization. Organizations exist to accomplish goals through strategies they craft and deploy. Coaching in the context of strategy assures that the executive has a clear sense of what he or she is trying to accomplish and sets the criteria for being a successful executive. A strategy is a succinct statement of what the executive hopes to accomplish and how resources will be applied to that purpose. Questions to clarify strategy include:

- What is your business trying to accomplish?

- Who are your primary customers? Why do they buy from you vs. a competitor?

- What are your two or three top priorities right now?

Step 2: Describe Your Personal Style

Every executive has a style or way of getting things done. This style is based on dozens of choices about how the executive makes decisions, processes information, treats people, and prefers working. The combination of these decisions form an identity for the executive that can often be captured in the image others have of the leader. Sometimes these images are crafted and positive; at other times, they are created by a sequence of actions. Sometimes these images help accomplish business goals; sometimes they do not. Each style has pluses and minuses. Each style may be modified by identifying and changing behaviors that lead to the style. Questions to address managerial style include:

- What is your managerial identity? How are you known by others? How would you like to be known by others? What is your Leadership Brand?

- What are your managerial strengths and weaknesses?

- How do you generally treat others, make decisions, handle conflict, manage information?

- In the middle circle of figure 1, you can write the strategy and style for the executive. This is at the heart of the coaching process.

Step 3: Define Stakeholders

Every executive gets work done through, with, and by others. These others may be considered stakeholders for the executive. The stakeholders often include those who might be above the executive (e.g., boss, boss’s boss, board of directors), those peers of the executive (e.g., executives in other units who participate in executive’s success), subordinates of the executive (e.g., employees or those who report directly or indirectly to the executive), and those outside the boundaries of the company (e.g., customers, suppliers, investors). These stakeholders may be identified by asking the executive who he must interact with to accomplish his work. The list may be stable over time or vary depending on assignment. Questions to define stakeholders include:

- Who must you interact with to reach your strategy?

- Who is affected by the work that you do?

- Who would you turn to in order to define your managerial style?

The stakeholders may be identified in each of the satellite circles in figure 1.

Step 4: Specify Goals for Each Stakeholder

Stakeholders have an interest in and impact on an executive’s success. To achieve a business strategy, each stakeholder must provide something (e.g., direct reports must become a cohesive team; employees overall must demonstrate commitment). Goals can be discussed for each stakeholder for the executive to deliver his strategy. Questions to specify stakeholder goals include:

- In the next period of time (three, six, twelve, or 24 months), what do you want to accomplish with each stakeholder?

- What does each stakeholder contribute to your ability to reach your strategy?

These goals for the stakeholders may be included in the satellite circles in figure 1.

Step 5: Prioritize Each Stakeholder and Goal

Not all things worth doing are worth doing well. Some things are more important than others. Some stakeholders and their goals are more central to executive success than others. Executives who try to relate equally all the time to all stakeholders end up serving none. Executives need to prioritize stakeholders based on how central they are to achieving business strategy. Strategies are timebound, and the key stakeholders for the next three months may be different than the stakeholders for the subsequent three months. For example, in an organization transformation, it might be critical in the next three months to get your direct reports on board with your agenda before going to the broader employee population in the subsequent three months. Questions to prioritize stakeholders and goals include:

- How important is each stakeholder for reaching your goal?

- How would you rate the importance of each stakeholder from 0 to 10 for the next period of time?

- How would you divide 100 points across the stakeholders to prioritize their impact on your strategies?

- How would you rank the stakeholders (from high to low) in terms of impact on your strategies?

These ratings may be placed on each satellite circle in figure 1.

Step 6: Allocate Time

Executives’ most valuable asset is their time. Where executives spend time communicates what matters most and sends signals to others about what they should do. Coaches can help leaders spend time by focusing on what executives can and should do with each stakeholder. When leaders are aware of how they have spent their time and have thought about where they should spend time, they make informed decisions. Involving other leaders in this coaching process can be helpful. In one case, a leader prioritized engaging employees in his strategy for the next six months (about 100 work days). He concluded that he should spend about fifteen days on this agenda. We invited the head of HR into the meeting and told him that the leader could invest fifteen days on communicating his vision in the next six months. We invited the HR leader to determine how to spend this resource in the most effective way. I have done similar work with heads of marketing and sales when the leader wants to spend time with customers, with heads of finance when the leader wants to connect better with the investment community, and so forth. Spending time thoughtfully turns ideas into actions. Questions to help leaders allocate time include:

- How much time in days do you think you should spend with each stakeholder given the priorities you have set?

- What specific behaviors and actions can you take with each stakeholder to accomplish your goals?

- How would these actions show up in your calendar? Remember that your calendar should probably be 30–40 percent unscheduled as events arise that merit attention, but the other 60–70 percent can be structured to ensure that you accomplish what matters most.

- How will you track your return on time invested?

In figure 1, you can begin to put time in days for each satellite circle.

Step 7: Determine Success

Wanting to succeed turns into success when it is measured. Unless strategies and goals are measured, they are fantasies and dreams. Measurements may be outcomes (what results) or behaviors (how things happen), but they should be specified. Coaches help determine measures of success that executives can track on their own. Questions to help determine successful measures include:

- How will you know you have succeeded in your overall strategy and in your goals with each stakeholder?

- How will you monitor your progress?

Combining behavior and strategy coaching into a personal leadership brand

Every leader has an identity, a reputation, or what we call a Leadership Brand.3 The Leadership Brand is a combination of both behavior and results. The behavioral coaching helps a leader recognize and develop his style, and the results coaching helps the leader focus on and deliver desired results. The combination of the two results is a personal Leadership Brand.

A personal Leadership Brand is an individual’s identity, reputation, or distinctiveness as a leader; it identifies strengths and predispositions, and includes provisions to mitigate the effects of weaknesses. Top management and other visible leaders often become known by their personal brand. In our teaching, we often put up pictures of famous leaders (Winston Churchill, Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Tony Blair, Charles de Gaulle, Golda Meir, Abraham Lincoln, and others) and ask participants to write down their impressions of these leaders’ personal brands. Despite some variety based on politics and country of origin, inevitably the resulting descriptions of these leaders’ personal brands display high congruence. Each of these leaders has a personal brand, one that is shared with the world and well-known, and that draws on the brand holder’s signature strengths.

An executive’s personal brand reflects both the behaviors and results. This personal identity becomes a reputation that others respond to and reinforce. Mature executives realize that over time, people will tend to forget some of the things leaders do (meetings attended, speeches given, goals set and accomplished), but they will remember the combination of these acts and the personal style that leaders demonstrate. Who we are speaks louder and longer than what we do and may even overpower real character flaws. But what we do is what creates our enduring brand. Winston Churchill’s enduring brand highlights his ability to rally citizens to fight in major world conflicts; it largely ignores his personal difficulties. Jack Welch will be remembered for his ability to create enormous wealth through strategic clarity and organization disciplines; his early “Neutron Jack” image is largely forgotten. Personal brand and signature strengths are hallmarks for executives.

As a result of behavior and strategy coaching, leaders should ultimately create strong and viable personal brands that distinguish them both inside and outside their company.

Challenges for Executives Being Coached

Being coached is not a trivial commitment. It requires that the executive be thoughtful and rigorous about the personal requirement for coaching. Executives who take on coaches to serve others will not likely change. Executives who accept someone else naming their coach for them will not likely bond with the coach. Executives who enter the coaching relationship without a clear agenda will likely end it without clear outcomes.

Before engaging with a coach, an executive should ask:

- Why am I interested in receiving coaching? Is it more behavioral or strategic results that interest me the most?

- Who wants me to get the coaching? What specific events have led them to recommend that I receive coaching?

- What will be the outcome of my coaching? How will I define success from this experience?

- How much is making behavior or strategic change a priority? Am I willing to invest both time and emotional energy to it?

- How much am I willing to be transparent to those I work with as I embark on the coaching exercise?

- What is the personal brand I now have and what would I like it to be? What price am I willing to pay to create this new brand?

Challenges for those Coaching Executives

Coaching is not a fallback career. It is not something you do because you have been an executive before, written an article, or observed others. Coaching requires a set of disciplines that draw on both psychology and organization that will help people change. Coaches should recognize their predisposition as either a behavior or strategy coach. Both require sensitivity to the other, but most coaches predominantly focus on one or the other. Coaches should learn their craft by being coached through self-learning and reflection, through mentoring from seasoned coaches, or through formal coaching of others. Coaches should be able to articulate their philosophy and approach to coaching so that they can make sure they are offering what clients most desire. Coaches should be willing to walk away from engagements that will not work and learn from those that do.

Conclusion

The noun of coach comes from having a coaching philosophy. This philosophy is based on maxims and beliefs of being a coach. The verb of coaching comes from a disciplined process for helping executives turn their aspirations to actions. Being a master coach means developing both a philosophy (noun) and process (verb) that will be uniquely tailored to you as a coach and to the person you are coaching. Coaching for results can focus on either behavior or strategy. Knowing one’s own approach enables the coach to better align with the client to make sure that coaching works. As a result of good coaching, leaders develop personal brands that distinguish them for all stakeholders—employees, customers, investors, and communities.

About the Author

Dave Ulrich has consulted and done research with over half of the Fortune 200. Dave was the editor of the Human Resource Management Journal 1990 to 1999, has served on the editorial board of four other journals, is on the Board of Directors for Herman Miller, is a Fellow in the National Academy of Human Resources, and is cofounder of the Michigan Human Resource Partnership.

References

A review of this work was presented at the 21st Annual SIOP (Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology), Dallas, Texas, April 2006, in a paper by Richard Arvey, Maria Rotundo, Wendy Johnson, Zhen Zhang, and Matt McGue entitled, Genetic and Environmental Components of Leadership Role Occupancy. The nature/nurture debate is also dealt within:

- Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., David T. Lykken, Matthew McGue, Nancy L. Segal, and Auke Tellegen, Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart, Science Magazine 250:4978 (1990).

- Judith Rich Harris, The Nuture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do (New York: The Free Press, 1998).

- Judith Rich Harris, Where Is the Child's Environment? A Group Socialization Theory of Development, Psycholofical Review 102:3 (1995).

- Matthew McGue, Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., William G. Iacono, and David T. Lykken, Behavioral Genetics of Cognitive Ability: A Life-Span Perspective, Nature, Nurture, and Psychology, ed. R. Plomin and G. E. McClearn (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1993)

The list of behavior coaching tips come from observing, listening to, and learning from great colleagues who have been my mentors and advisors: including Wayne Brackbank, Ralph Christensen, Bob Eichinger, Marshall Goldsmith, Francis Hesselbein, Steve Kerr, Dale Lake, Paul McKinnon, Bonner Ritchie, Norm Smallwood, Paul Thompson, Warren Wilhelm, and Jack Zenger. It is difficult to attribute any one idea to any one person, but I am indebted to each of these colleagues for these ideas.

The work on personal brand has been discussed by Tom Peters, The Brand You 50: Or Fifty Ways to Transform Yourself From an “Employee” into a Brand That Shouts Distinction, Commitment, and Passion! (New York: Knopf, 1999)

Turning this personal brand into a Leadership Brand can be found in Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood Leadership Brand: Developing Customer Focused Leaders to Drive Performance and Build Lasting Value (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2007).

This worksheet allows you to conceptualize how to approach executive coaching with the following outline:

- Strategy and Style for the executive being coached.

- Stakeholder(s) identified.

- Rating of the impact of the stakeholder(s).

- Time in days to spend with stakeholder(s) given the priorities and ratings.

- The measure of success or how success is determined in relation to the stakeholder(s).

A coaching philosophy underpins both receiving and giving coaching. Coaching does not mean doing but helping get things done.

Coaching has become one of those catch-all phrases like strategy, quality, or process. Because of its popularity, coaching has sometimes been misused. Those who use coaches sometimes are more excited about the prospect of being coached than about changing. One executive who was advised by his board to find a coach confessed after about 60 minutes of the first coaching session that he was really interested in engaging a “celebrity coach.” He could then tell his board and peers that he was being coached by a well-known coach which would give more credence to his leadership. Needless to say, coaching meant little to him and few competent coaches would succumb to work with him. This is like having a strategy or quality off-site training, but knowing that little will really change after the event. At times, those who declare themselves coaches are only a little more committed. When executives who retire early move into coaching as a transitory state between jobs, they fail to bring rigor to the role.

To overcome such generalities and misuses, coaching needs to move from platitudes to greater professionalism. Making coaching more professional requires a clear definition of the results of coaching. Coaching is not merely about a process of finding someone to confer but should have clear results that define the outcome of the engagement. In this article, I will suggest that there are two general coaching results: behavior change and strategy realization. Behavior change means that the executive being coached has behavioral predispositions that get in the way of being an effective executive. When specific behaviors are identified, examined, and modified, coaches help executives change. Strategy realization means that the executive being coached needs help to clarify and focus the business strategy to help the business achieve financial, customer, or organization goals. Of course, good coaching results are neither behavioral or strategy focused but require both for long-term results. When both exist, coaching helps craft an executive’s personal brand or identity that combines both personal behaviors and outcomes. But it is helpful to examine the premises of both behavior and strategy coaching so that they can be combined to help executives determine their personal brand.

This article begins with the basic philosophy of coaching required for either behavior or strategy results. It then discusses key tenants and an approach for both behavior and strategy coaching, then concludes with challenges for executives who want coaching for results and coaches who want to deliver results.

Philosophy of Coaching

A coaching philosophy underpins both receiving and giving coaching. Coaching does not mean doing but helping get things done. Coaches help athletes play the game better, even if they do not personally play the game. Player-coaches generally do not perform as well as sideline coaches. Executive coaches may not be the best managers, but they must be observers of good management behaviors and motivators for improved performance. In most coaching assignments, I try to observe a leader at work. In team meetings, I note how he interacts before the meeting (e.g., Is he formal or informal? Do people approach him or not?), how he manages a meeting (e.g., Does he follow an agenda? How does he make decisions? How does he treat the people during the meeting?), and how he follows up after the meeting (e.g., How does he check up on the decisions made during the meeting?). These observations come from observing the nuances of behavior and their consequences.

Coaching is not about the coach but about the person being coached. Being able to help someone recognize their strengths and weaknesses and how they can improve requires that the coach be a facilitator, not owner, of change. The executive being coached has to own and accept both his good and bad behavior. Coaches won’t make change happen or stick; they will simply help set conditions and circumstances that help others change. To keep ownership focused on the client, I keep asking them, “What do you want?” and then try to show them that their behaviors are unlikely to lead them to their goals. Clients define the desired outcomes and then we work together to help them reach their goals.

Coaching is both a learned art from experience and a disciplined science from education. Becoming a legitimate coach is a catch-22. Those you coach must have confidence in you, yet you don’t earn confidence until you have coached others. Early coaching experiences may begin with friends and allies who trust you and whom you can help and counsel. Like sports coaches who learn from being assistant coaches at high school or college levels before becoming head coaches in the pros, management coaches master their craft from working in the managerial trenches. My early coaching was often with those whom I had known in other settings (e.g., an executive from an executive development course) who trusted me. Over time, as I matured as a coach from successes and failures, I was more likely to be invited to coach those whom I did not know beforehand.

Coaching is ultimately a relationship. Sometimes the smartest and most technically proficient people are not necessarily the best coaches. Coaching requires sharing information and ideas in ways that change behavior and accomplish strategies. Coaches are not measured by what they know but how they help others change because of what they know and do. Transfer of knowledge flows from relationships of trust, so coaches must be credible and trusted by those they coach. In most of my coaching relationships, we start by getting to know each other. This requires listening and learning to understand the person I am coaching and sharing with them some of who I am. Building a personal bond and professional affection founds the coaching process. In many coaching assignments, we have begun by talking about a wide array of personal issues including hobbies, families, and personal goals. Once the executive knows I care about him or her personally, we can begin the more rigorous process of executive coaching. Until a relationship of trust is forged, coaching is more rhetoric than results.

Coaches may be from inside or outside the company. Those from inside know the subtleties of the company, the network of relationships within the company, and the likely impact of their counsel. Those from outside the company often have credibility based on external validity, bring innovative ideas to the coaching experience, and may be candid when insiders might temper their remarks. For internal coaches to be credible, they must develop an independent streak; for external coaches to succeed, they must discern organizational nuances. Most of my coaching has been from the outside as an external consultant, but in many cases, I have partnered with an internal coach (e.g., HR professional) who would help the business leader in more day-to-day routine transactions while I would do episodic coaching around events or in predictable time frames (e.g., every six or twelve weeks).

Coaches may not be popular. Giving blunt feedback about behavior or strategies may be personally risky at times. Giving feedback helps only if the feedback helps the receiver change behavior and accomplish goals. Often executives self-delude themselves because too few have been honest with them or because their self-confidence overwhelms their self-awareness. Constructive feedback concentrates on behaviors not the person, focuses on the future more than the past, and helps the person self-discover. I recall having collected 360 data from a leader where the data showed significant concerns. I set the stage for sharing this data by reminding him that without struggles, we do not make progress, and that only through honest looks in the mirror can anyone improve. Then we examined the data together and non-defensively worked to figure out why it was given as it was, what it meant in terms of his behaviors, and how he could productively respond. The concept that “we judge ourselves by our intent and others judge us by our behavior” has been useful. This philosophy has helped me coach executives and has helped them see that their intent may have been to clarify and focus attention, but their rather abrupt and direct questioning of employees may have communicated a lack of sensitivity and concern. Coaches must bring unfavorable views to the surface and deal with negative data in helpful ways.

Coaches probe through questions that require self-reflection. Learning is more powerful when the learner learns by choice rather than by edict. Coaches who pose insightful and timely questions help executives see the impact of their behavior on others thus helping executives improve. Some of my favorite questions are “What do you want?” to help focus on goals and purposes; “What are the options?” to generate out-of-the-box alternatives and become real; “What are the first steps?” to turn ideas into practices; “How would you know?” to define measurable outcomes; and “What is the decision you can make now to make progress?” to focus attention. These and other questions help the coach engage the client in reflection so that the client owns the result and the process of achieving the result.

These maxims form a coaching philosophy that enables a coach to help an executive deliver both behavioral and strategic results.

Behavior Results

Changing behavior is not easy. We know from research that about 50 percent of an individual’s values, attitudes, and behaviors come from DNA and heritage; the other 50 percent are learned over time.1 This split means that while we each have predispositions, we can also learn new behaviors. I am predisposed to be an introvert, to find energy in quiet personal moments, and to avoid social crowds and public settings. Yet, I do presentations for a living where I have learned to engage with others in extroverted ways. When working to help leaders change behaviors, it is helpful for them to recognize their predispositions but not to be bound by them. One executive preferred the more private anonymity that came from forging close personal relationships with his team and those he worked with. But, when his company was under siege, he realized that someone had to be the face of the company to the public. While not predisposed to this role, he accepted the challenge and worked to prepare and deliver public support for the company. While he became quite gifted at the public role—appearing on news programs, being interviewed by the media, and even doing commercials—he was never fully comfortable in it. An implication of the 50-50, nature-nurture, born-bred debate is that while the past sets conditions on our behavior, our behavior is not preconditioned. Any leader can modify behavior through effective coaching. Below are some of the hints for doing coaching for behavioral results.2

Know Why

Until there is a need for change, change will not occur. Once clients understand why they should change, they are more likely to accept what they should change. One senior executive had been promoted quickly due to his talents for analytics and detail. He was renowned for high-quality work. But, when he became the general manager of a large division, his attention to detail and analytics kept him from doing the more generic strategy work required in his new role. In our early coaching work, it was clear that he was more predisposed to working on details than strategy. To help him transition into his general manager role, we spent time defining the competencies of a successful general manager. As he benchmarked himself against the competencies we defined, he realized his strategic short comings and was more willing to explore new behaviors required to fulfill his new role.

Collect Data

Often single events or observations from single individuals are episodes not patterns. Coaching should be about patterns. Generally, people can identify their strengths more than their weaknesses, and collecting data from others helps face a true reality. Leadership 360s provide a marvelous source of data. The 360 may be through interviews or a survey of an executive’s subordinates, peers, and supervisors. With full spectrum data, the 360 will provide a wholistic view of the executive’s relationships and highlight areas of strength and weakness. 360 data enables the executives to compare self-perception to the perceptions of different stakeholders (e.g., Does the executive manage up or down better than across?). Another source of data is to track executive time. In one coaching engagement, the executive wanted to be more customer-centric. So, for two weeks, she kept a time log of who she spent time with, where she spent time, and what issues she spent time on. This time log was somewhat like a personal video or like someone who wants to lose weight writing down everything they eat. It was quite easy to review the data with the executive and observe she tended to respond to requests more than proactively investing her time. And, customer requests were low on her demand list. The data from a 360 or a time log helps the executive more accurately see what changes can and should be made. This data also serves as a baseline to track improvements that may be obtained through the coaching.

Prioritize

Not everything worth changing can or should be changed. In behavior coaching, it is critical to identify the one or two key behaviors that most need to be changed and that will have the most impact. One executive was losing credibility with his peers and the head of the company. In interviews, a number of concerns came up, including his lack of ability to engage others, his inability to focus, and his lack of tact in communicating desires. But, when asked “What one thing should he work on to be a more effective leader?” the response consistently was to be more brief in his comments. Evidently, the executive had a tendency to give long-winded answers to seemingly simple questions. With this input, the executive prioritized brevity as a behavior change. He started to track how long he spoke in meetings and other forums. He tried to keep his remarks to less than 45 seconds. His trusted administrative assistant gave him daily feedback of how often he kept to his 45 second rule. He improved and as he spoke less people sensed that he listened more. There is a silly line in change that applies to prioritizing behaviors: “By the yard it’s hard, by the inch it’s a cinch.” Some troubled executives have many things to work on, but they should find one or two specific behaviors that will be visible, impactful, and doable.

Be Behavioral

Abstract goals will result in abstract changes; specific behavior goals will result in specific changes. Sometimes the results of interviews are generic: “She is not a good people person.” In these cases, it is important to go deeper and identify specific behaviors that cause the conclusion. Deeper probes generally focus on situations: “Can you think of a situation where she treated people poorly? What specifically did she do? What could or should she have done differently?” Behaviors are observable and visible. I have asked executives to envision someone following them around with a video camera. What behaviors would the video expose? In becoming better with people, the video might reveal the executive not looking at people she talks to, not calling them by name, not paying attention when others comment, and being quickly distracted when in conversation. One executive learned that he went too often to his BlackBerry®. When he felt he had what he needed from a conversation, his mind would wander and he would look at his BlackBerry® for other incoming messages. This simple behavior communicated to his subordinates that he was not focused on them. By recognizing this behavior, he was able to limit it.

Focus on the Future More than the Past

Coaching is not therapy. In cognitive or psychoanalytic therapy, the therapist works to identify underlying causes of a behavior. Often these causes are masked, but rooted in past experiences or previous relationships with parents or others. Competent therapists have the ability to uncover and unlock how the past affects the present. Coaches do not need to be therapists to focus on behavioral change. Behavior coaching identifies what behaviors are causing dysfunctions then focuses the executive on the future and how to behave differently. An executive who wants to improve customer relationships needs to prepare an anticipatory time log where time with customers and on customer issues is woven into the calendar. An executive who wants to improve in people skills can learn to ask more personal questions of employees and peers, to focus full-time attention on the employee they are interacting with, and to express gratitude for an employee’s good work. These behavior changes generally do not require the intense psychoanalytic work a therapist might provide.

Go Public

Commitment goes up when we go public and become personally transparent with our intentions and desires. When an executive has identified an area to improve, it is helpful for the executive to share this commitment with others. This may be in a staff meeting where the executive thanks the staff for being candid with the coach in interviews then shares with the staff the conclusions from the interviews and publicly states what she will work on. This transparency lets the team know that the executive has heard their comments and is working to improve a specific behavior. In almost all cases, executives who are personally transparent will engender respect and confidence from their peers and subordinates as they work to change their behavior. The executive who savored details told his team that he knew he would rather be doing the detailed work but that he was going to commit to spending less time on details and more time on vision and strategy. He asked that his team make sure that the details were done well so he could focus on the longer-term issues. He also asked his team to quietly remind him when he was falling back into his detail traps.

Find Support

It is hard to clap with one hand and it is hard to change by oneself. Almost every executive I have seen who has made behavioral changes has had enormous support from trusted advisors. Many executives have an administrative assistant who is in constant contact with the executive. I frequently invite executives to engage their administrative assistant to give them daily or weekly views of how well the executive is adopting new behaviors. Executives open to such input will be much more likely to change. It is often difficult for high-powered and successful leaders to hear criticism, but when they ask for it and when it is framed as support for future success, they are more prone to listen and act. At times, it is also very helpful to have support from non-work friends since behaviors at work and at home are often the same. Executives who share with their spouse or children what they are working on often find enormous support.

Start Small, Keep Going

Most large change starts with small steps. Once executives have picked a behavior that they want to change, I have found “four threes” a helpful way to embed the behavioral change.

- Three hours. In the next three hours what can you do to exhibit the new behavior? This is probably not something dramatic but should be specific.

- Three days. In the next three days, what can you do to demonstrate sustained commitment to the new behavior? Quietly but consistently practice the new behavior. This may affect what you read, your language, your personal demeanor, and the way you relate to others.

- Three weeks. In the next three weeks, make sure that the new behavior change shows up in activities and relationships. Calendar times when the behavior change will be evident (e.g., dedicating time with customer groups or a brief staff meeting to talk about work processes). Continue to practice the new behaviors and receive frequent feedback on how you are doing.

- Three months. After about three months of working on the new behavior, if you continue with it, it begins to become part of your identity, and others will treat you accordingly. When your leadership identity, brand, or reputation becomes something others expect in you, you will be more likely to live it.

Like all new things, at first, the new behaviors may be difficult, but after three months, they become a redefinition of your personal brand. As others come to expect things of you, they begin to be more natural.

Learn

Learning should be less an event (let’s go off-site and talk to each other) and more a natural process. The best learners are inquisitive, self-reflective, and adaptive. They are constantly asking what works and what does not, then trying to put those insights into a future context. Executives who demonstrate learning agility are more likely to succeed. Overtime, coaches should be replaced by self-observation. When executives have the capacity to self-observe and self-regulate, they learn and grow. Sometimes this learning can be formalized through after action reviews where executives debrief their teams on how they perform, and at other times, it may be more personal where executives write in a journal, have a personal tally sheet, or share with a friend what they are learning.

Follow Up

Finally, behavior coaching needs indicators of progress. The greatest success is when the executive can track behavioral change. This is why data collection early in a coaching engagement is so important. Readministering a 360, redoing interviews, or debriefing the behavior change process enables an executive to monitor progress. If behavior change did not occur, the coach did not fulfill his assignment. Marshall Goldsmith boldly states that he is not paid unless the executive changed behavior as seen by others. This is not just clever marketing, but a real dedication to making sustained behavior change happen.

Coaching for behavior change changes behaviors. The end result is that the leader personalizes a new set of behaviors that may work for him. As learned behaviors become natural acts, leaders change their identities and reputations.

Strategy Results Process

Strategy results coaching focuses more on helping the executive gain clarity about the results he hopes to accomplish and how to make them happen. It is less psychological and more organizational. It also builds on the philosophy of trust, relationship, and collaboration, but focuses this philosophy on helping the executive clarify and reach his goals. In my strategy coaching, I have adapted the following steps depending on the situation. Figure 1 is the summary of this coaching process. At first glance, this is a complex figure, but each step enables me to draw and build this figure and coach a client through a behavior or strategy process.

Step 1: Clarify Your Business or Organization Strategy

Every executive works for an organization. Organizations exist to accomplish goals through strategies they craft and deploy. Coaching in the context of strategy assures that the executive has a clear sense of what he or she is trying to accomplish and sets the criteria for being a successful executive. A strategy is a succinct statement of what the executive hopes to accomplish and how resources will be applied to that purpose. Questions to clarify strategy include:

- What is your business trying to accomplish?

- Who are your primary customers? Why do they buy from you vs. a competitor?

- What are your two or three top priorities right now?

Step 2: Describe Your Personal Style

Every executive has a style or way of getting things done. This style is based on dozens of choices about how the executive makes decisions, processes information, treats people, and prefers working. The combination of these decisions form an identity for the executive that can often be captured in the image others have of the leader. Sometimes these images are crafted and positive; at other times, they are created by a sequence of actions. Sometimes these images help accomplish business goals; sometimes they do not. Each style has pluses and minuses. Each style may be modified by identifying and changing behaviors that lead to the style. Questions to address managerial style include:

- What is your managerial identity? How are you known by others? How would you like to be known by others? What is your Leadership Brand?

- What are your managerial strengths and weaknesses?

- How do you generally treat others, make decisions, handle conflict, manage information?

- In the middle circle of figure 1, you can write the strategy and style for the executive. This is at the heart of the coaching process.

Step 3: Define Stakeholders

Every executive gets work done through, with, and by others. These others may be considered stakeholders for the executive. The stakeholders often include those who might be above the executive (e.g., boss, boss’s boss, board of directors), those peers of the executive (e.g., executives in other units who participate in executive’s success), subordinates of the executive (e.g., employees or those who report directly or indirectly to the executive), and those outside the boundaries of the company (e.g., customers, suppliers, investors). These stakeholders may be identified by asking the executive who he must interact with to accomplish his work. The list may be stable over time or vary depending on assignment. Questions to define stakeholders include:

- Who must you interact with to reach your strategy?

- Who is affected by the work that you do?

- Who would you turn to in order to define your managerial style?

The stakeholders may be identified in each of the satellite circles in figure 1.

Step 4: Specify Goals for Each Stakeholder

Stakeholders have an interest in and impact on an executive’s success. To achieve a business strategy, each stakeholder must provide something (e.g., direct reports must become a cohesive team; employees overall must demonstrate commitment). Goals can be discussed for each stakeholder for the executive to deliver his strategy. Questions to specify stakeholder goals include:

- In the next period of time (three, six, twelve, or 24 months), what do you want to accomplish with each stakeholder?

- What does each stakeholder contribute to your ability to reach your strategy?

These goals for the stakeholders may be included in the satellite circles in figure 1.

Step 5: Prioritize Each Stakeholder and Goal

Not all things worth doing are worth doing well. Some things are more important than others. Some stakeholders and their goals are more central to executive success than others. Executives who try to relate equally all the time to all stakeholders end up serving none. Executives need to prioritize stakeholders based on how central they are to achieving business strategy. Strategies are timebound, and the key stakeholders for the next three months may be different than the stakeholders for the subsequent three months. For example, in an organization transformation, it might be critical in the next three months to get your direct reports on board with your agenda before going to the broader employee population in the subsequent three months. Questions to prioritize stakeholders and goals include:

- How important is each stakeholder for reaching your goal?

- How would you rate the importance of each stakeholder from 0 to 10 for the next period of time?

- How would you divide 100 points across the stakeholders to prioritize their impact on your strategies?

- How would you rank the stakeholders (from high to low) in terms of impact on your strategies?

These ratings may be placed on each satellite circle in figure 1.

Step 6: Allocate Time

Executives’ most valuable asset is their time. Where executives spend time communicates what matters most and sends signals to others about what they should do. Coaches can help leaders spend time by focusing on what executives can and should do with each stakeholder. When leaders are aware of how they have spent their time and have thought about where they should spend time, they make informed decisions. Involving other leaders in this coaching process can be helpful. In one case, a leader prioritized engaging employees in his strategy for the next six months (about 100 work days). He concluded that he should spend about fifteen days on this agenda. We invited the head of HR into the meeting and told him that the leader could invest fifteen days on communicating his vision in the next six months. We invited the HR leader to determine how to spend this resource in the most effective way. I have done similar work with heads of marketing and sales when the leader wants to spend time with customers, with heads of finance when the leader wants to connect better with the investment community, and so forth. Spending time thoughtfully turns ideas into actions. Questions to help leaders allocate time include:

- How much time in days do you think you should spend with each stakeholder given the priorities you have set?

- What specific behaviors and actions can you take with each stakeholder to accomplish your goals?

- How would these actions show up in your calendar? Remember that your calendar should probably be 30–40 percent unscheduled as events arise that merit attention, but the other 60–70 percent can be structured to ensure that you accomplish what matters most.

- How will you track your return on time invested?

In figure 1, you can begin to put time in days for each satellite circle.

Step 7: Determine Success

Wanting to succeed turns into success when it is measured. Unless strategies and goals are measured, they are fantasies and dreams. Measurements may be outcomes (what results) or behaviors (how things happen), but they should be specified. Coaches help determine measures of success that executives can track on their own. Questions to help determine successful measures include:

- How will you know you have succeeded in your overall strategy and in your goals with each stakeholder?

- How will you monitor your progress?

Combining behavior and strategy coaching into a personal leadership brand

Every leader has an identity, a reputation, or what we call a Leadership Brand.3 The Leadership Brand is a combination of both behavior and results. The behavioral coaching helps a leader recognize and develop his style, and the results coaching helps the leader focus on and deliver desired results. The combination of the two results is a personal Leadership Brand.

A personal Leadership Brand is an individual’s identity, reputation, or distinctiveness as a leader; it identifies strengths and predispositions, and includes provisions to mitigate the effects of weaknesses. Top management and other visible leaders often become known by their personal brand. In our teaching, we often put up pictures of famous leaders (Winston Churchill, Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Tony Blair, Charles de Gaulle, Golda Meir, Abraham Lincoln, and others) and ask participants to write down their impressions of these leaders’ personal brands. Despite some variety based on politics and country of origin, inevitably the resulting descriptions of these leaders’ personal brands display high congruence. Each of these leaders has a personal brand, one that is shared with the world and well-known, and that draws on the brand holder’s signature strengths.

An executive’s personal brand reflects both the behaviors and results. This personal identity becomes a reputation that others respond to and reinforce. Mature executives realize that over time, people will tend to forget some of the things leaders do (meetings attended, speeches given, goals set and accomplished), but they will remember the combination of these acts and the personal style that leaders demonstrate. Who we are speaks louder and longer than what we do and may even overpower real character flaws. But what we do is what creates our enduring brand. Winston Churchill’s enduring brand highlights his ability to rally citizens to fight in major world conflicts; it largely ignores his personal difficulties. Jack Welch will be remembered for his ability to create enormous wealth through strategic clarity and organization disciplines; his early “Neutron Jack” image is largely forgotten. Personal brand and signature strengths are hallmarks for executives.

As a result of behavior and strategy coaching, leaders should ultimately create strong and viable personal brands that distinguish them both inside and outside their company.

Challenges for Executives Being Coached

Being coached is not a trivial commitment. It requires that the executive be thoughtful and rigorous about the personal requirement for coaching. Executives who take on coaches to serve others will not likely change. Executives who accept someone else naming their coach for them will not likely bond with the coach. Executives who enter the coaching relationship without a clear agenda will likely end it without clear outcomes.

Before engaging with a coach, an executive should ask:

- Why am I interested in receiving coaching? Is it more behavioral or strategic results that interest me the most?

- Who wants me to get the coaching? What specific events have led them to recommend that I receive coaching?

- What will be the outcome of my coaching? How will I define success from this experience?

- How much is making behavior or strategic change a priority? Am I willing to invest both time and emotional energy to it?

- How much am I willing to be transparent to those I work with as I embark on the coaching exercise?

- What is the personal brand I now have and what would I like it to be? What price am I willing to pay to create this new brand?

Challenges for those Coaching Executives

Coaching is not a fallback career. It is not something you do because you have been an executive before, written an article, or observed others. Coaching requires a set of disciplines that draw on both psychology and organization that will help people change. Coaches should recognize their predisposition as either a behavior or strategy coach. Both require sensitivity to the other, but most coaches predominantly focus on one or the other. Coaches should learn their craft by being coached through self-learning and reflection, through mentoring from seasoned coaches, or through formal coaching of others. Coaches should be able to articulate their philosophy and approach to coaching so that they can make sure they are offering what clients most desire. Coaches should be willing to walk away from engagements that will not work and learn from those that do.

Conclusion

The noun of coach comes from having a coaching philosophy. This philosophy is based on maxims and beliefs of being a coach. The verb of coaching comes from a disciplined process for helping executives turn their aspirations to actions. Being a master coach means developing both a philosophy (noun) and process (verb) that will be uniquely tailored to you as a coach and to the person you are coaching. Coaching for results can focus on either behavior or strategy. Knowing one’s own approach enables the coach to better align with the client to make sure that coaching works. As a result of good coaching, leaders develop personal brands that distinguish them for all stakeholders—employees, customers, investors, and communities.

About the Author

Dave Ulrich has consulted and done research with over half of the Fortune 200. Dave was the editor of the Human Resource Management Journal 1990 to 1999, has served on the editorial board of four other journals, is on the Board of Directors for Herman Miller, is a Fellow in the National Academy of Human Resources, and is cofounder of the Michigan Human Resource Partnership.

References

A review of this work was presented at the 21st Annual SIOP (Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology), Dallas, Texas, April 2006, in a paper by Richard Arvey, Maria Rotundo, Wendy Johnson, Zhen Zhang, and Matt McGue entitled, Genetic and Environmental Components of Leadership Role Occupancy. The nature/nurture debate is also dealt within:

- Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., David T. Lykken, Matthew McGue, Nancy L. Segal, and Auke Tellegen, Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart, Science Magazine 250:4978 (1990).

- Judith Rich Harris, The Nuture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do (New York: The Free Press, 1998).

- Judith Rich Harris, Where Is the Child's Environment? A Group Socialization Theory of Development, Psycholofical Review 102:3 (1995).

- Matthew McGue, Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., William G. Iacono, and David T. Lykken, Behavioral Genetics of Cognitive Ability: A Life-Span Perspective, Nature, Nurture, and Psychology, ed. R. Plomin and G. E. McClearn (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1993)

The list of behavior coaching tips come from observing, listening to, and learning from great colleagues who have been my mentors and advisors: including Wayne Brackbank, Ralph Christensen, Bob Eichinger, Marshall Goldsmith, Francis Hesselbein, Steve Kerr, Dale Lake, Paul McKinnon, Bonner Ritchie, Norm Smallwood, Paul Thompson, Warren Wilhelm, and Jack Zenger. It is difficult to attribute any one idea to any one person, but I am indebted to each of these colleagues for these ideas.

The work on personal brand has been discussed by Tom Peters, The Brand You 50: Or Fifty Ways to Transform Yourself From an “Employee” into a Brand That Shouts Distinction, Commitment, and Passion! (New York: Knopf, 1999)

Turning this personal brand into a Leadership Brand can be found in Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood Leadership Brand: Developing Customer Focused Leaders to Drive Performance and Build Lasting Value (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2007).

This worksheet allows you to conceptualize how to approach executive coaching with the following outline:

- Strategy and Style for the executive being coached.

- Stakeholder(s) identified.

- Rating of the impact of the stakeholder(s).

- Time in days to spend with stakeholder(s) given the priorities and ratings.

- The measure of success or how success is determined in relation to the stakeholder(s).